During the latter half of the 19th century there were a number of makers of underhammer target rifles, two of the most notable among them were the famous New York gunmaker, William Billinghurst, and to a lesser degree, his contemporary, David H. Hilliard of Cornish, New Hampshire. Yes, there were many more makers of underhammer target rifles but I would like to draw your attention to these two for a moment.

Both produced fine examples of underhammer target rifles, although quite different in their basic designs. A Google search will provide info and photos of their outstanding work for those who don't mind a bit more snooping.

Today there are a few underhammer makers who have taken some of the older designs and added their own thoughts, ideas and improvements. One such gunmaker is Tilo Dedinski of Kulback, Germany. Inspired by the work of Billinghurst, Mr. Dedinski has produced a first-class modern-day Billinghurst that has proven its worth by taking gold in international competition.

His "Billinghurst," seen here in its offhand version, is available in two configurations and calibers intended for 50-meter and 100-meter matches. You may wish to visit his website: www.dedinski.com for more information on his full line of underhammer arms.

His "Billinghurst," seen here in its offhand version, is available in two configurations and calibers intended for 50-meter and 100-meter matches. You may wish to visit his website: www.dedinski.com for more information on his full line of underhammer arms. While some makers have chosen to emulate Billinghurst's designs, it seems that the underhammer designs of Hilliard have inspired a number of other modern European gunmakers to produce and offer their own versions of his justly famous target rifles as seen in the photo to the left.

While some makers have chosen to emulate Billinghurst's designs, it seems that the underhammer designs of Hilliard have inspired a number of other modern European gunmakers to produce and offer their own versions of his justly famous target rifles as seen in the photo to the left.Although Europeans developed their own underhammmer systems, they have long admired the features represented in American underhammer designs and the quality of materials and construction employed by them indicates the respect that they have for American underhammers.

The Italian Artax is a very modern rendition of the percussion underhammer system and is more evidence that the underhammer concept and its development is still alive and well, both here and abroad. Below is the more traditional Artax underhammer target rifle. Unfortunately, there are no current U.S. distributors of what appears to be a very fine rifle. Clicking on the photo will allow a detailed view of the Artax. Clicking the Back button at the top left of your screen will return you to the text.

During the War Between the States, underhammer rifles were used quite successfully by a number of snipers and I believe it was the underhammer's performance on the battlefield that may have lead to their post-war use and development as target rifles.

Some have asked me about producing a (smaller bore) underhammer rifle with more influence of a target rifle than a hunting rifle. While I prefer crafting hunting rifles, I have made some rather wild target rifles based on the underhammer system, the most extreme being a .54 calibre offhand schuetzen rifle.

A reader of this blog had asked if I had photos of any of the underhammer target rifles that I had made. As it turns out, the only one that I bothered to document with photos is that schuetzen. I have included them below as an example of what can be done for anyone who wishes to venture down that road.

Good luck!

The exaggerated features of the schuetzen rifle are designed to provide the perfect ergonomic fit of rifle to shooter for 200-yard offhand shooting. The idea being that the shooter simply stands in a comfortable, unstrained offhand pose and the rifle fits the pose perfectly.

In my version the forearm provides a palm rest that keeps the left hand away from the upward swinging hammer. Or if the shooter is one who rests the forearm on his finger tips, there is a thumb hollow on the bottom of the forearm which makes for a secure support when using that hold.

While perhaps not a beauty to most, it's a pretty face that any schuetzen shooter can admire.

The extreme sculpted cheekpiece provides a very comfortable face-fitting support while the light Swiss buttplate helps hold the rifle firmly on the shoulder. This buttplate is actually quite large and flat and distributes recoil very well making the 20-shot string less fatiguing and more comfortable to shoot.

The extreme sculpted cheekpiece provides a very comfortable face-fitting support while the light Swiss buttplate helps hold the rifle firmly on the shoulder. This buttplate is actually quite large and flat and distributes recoil very well making the 20-shot string less fatiguing and more comfortable to shoot. Coupled with the unusual forward-arcing finger rest, the well-proportioned thumb rest on the right side of the buttstock allows full control of the rifle by the right hand while still isolating trigger finger motion from adverse influence on the rifle while squeezing off the shot.

Coupled with the unusual forward-arcing finger rest, the well-proportioned thumb rest on the right side of the buttstock allows full control of the rifle by the right hand while still isolating trigger finger motion from adverse influence on the rifle while squeezing off the shot.Again, ergonomics is the name of the game when designing the schuetzen rifle

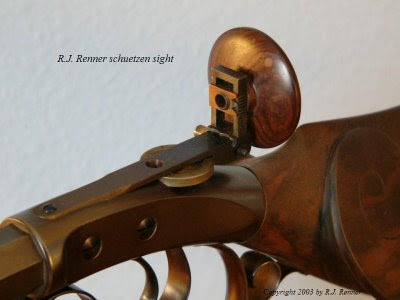

Good sights are essential for 200-yard offhand shooting. Turning the sight disk (yes, it's wood) loosens it and allows course adjustment to get your shots on target quickly, while the calibrated thumbwheel allows for finer tuning to zero the shot. A windage adjustment screw is also provided at the rear of the tang on the right side of the sight.

Good sights are essential for 200-yard offhand shooting. Turning the sight disk (yes, it's wood) loosens it and allows course adjustment to get your shots on target quickly, while the calibrated thumbwheel allows for finer tuning to zero the shot. A windage adjustment screw is also provided at the rear of the tang on the right side of the sight.The round "window" on the tang of the sight allows viewing the number settings stamped on the thumbwheel for exact repeatability in sight adjustment.

At the muzzle there is a very fine bead sight protected by an ample globe. Together with this rear aperture sight, they create the clear and precise sight picture necessary to win at this game.

Because this rifle is strictly a range rifle, loading is accomplished with a range rod, hence no ramrod, which simplified construction.

Combining the ultra fast underhammer mechanism with a good solid offhand shooting platform such as the schuetzen seen here, resulted in a very accurate rifle. And while strange looking to the novice, these rifles handle like a dream and will out-shoot the capabilities of most shooters.

Clicking on any of the images will enlarge them for easier study of details. Clicking the "Back" arrow will bring you back to the text.

While it's all the rage to shoot sabots and smaller bore bullets these days, I haven’t seen that all the extra fuss and gadgets have actually made for better hunters or more game in the freezer. Now don‘t get me wrong - I love to experiment, too. But, when reloading for a follow-up shot becomes so complicated or difficult that it takes your attention from the running and/or wounded game animal and has you futzing around trying to get a sabot started into the muzzle nice and straight (and then hope your bullet was properly seated therein), then straining your milk while trying to push that hard plastic pill down the bore with a too-thin ramrod all while your hands are probably cold, wet, stiff, or all the above, I can’t see any advantage.

While it's all the rage to shoot sabots and smaller bore bullets these days, I haven’t seen that all the extra fuss and gadgets have actually made for better hunters or more game in the freezer. Now don‘t get me wrong - I love to experiment, too. But, when reloading for a follow-up shot becomes so complicated or difficult that it takes your attention from the running and/or wounded game animal and has you futzing around trying to get a sabot started into the muzzle nice and straight (and then hope your bullet was properly seated therein), then straining your milk while trying to push that hard plastic pill down the bore with a too-thin ramrod all while your hands are probably cold, wet, stiff, or all the above, I can’t see any advantage.